Cultivate and walk the Way, and never seek outside,

The hidden cause is just the wisdom-nature of the mind.

White billows soar to heaven and the black breakers subside,

Now to the other shore, Nirvana, effortlessly climb.

Don’t miss another chance, return, return, time after time,

Take care, take care, attentive to this innocence divine,

The news arrives in shadows, shadows hazy through the blind,

In fleeting, fleeting glances, the inherently sublime.

–Master Hsuan Hua, Verses on the Heart Sutra

How does a verse communicate all of its meanings to us?

With midterm break just beginning, I’ll be spending the week contemplating and reciting Guan Yin’s name. In some sense I feel that for every session I have to reorient myself to practice, and of course, exactly what this means is different every time. Luckily, my recent classes have been providing a lot of food for thought. In our Avatamsaka Sutra class, we spent the last several weeks translating verses about spiritual practices. There has been quite a bit of discussion about their meaning, as well as about literary style and accuracy. How does a verse communicate all of its meanings to us? What is the experiential difference between reading prose and chanting verse, and how does this affect our consciousness?

Translation for me, like spiritual cultivation, has become a constant balancing act between strict discipline, focus, creativity, learning, and of course humility, as the ego tends to always show its face. In our Heart Sutra class this semester, we focused on commentary by Master Hua, also written in verse. On of my favorite verses is the exhortation for practice above—and seeing that the Sutra was spoken by Guan Yin Bodhisattva, I thought it might be an appropriate verse to inspire aspirations for the spring Guan Yin Session.

The atmosphere was alert, clear, and crisp, yet quiet and pleasant. The spirit of shared collected effort across the campus gave it a sense of not solitude, not loneliness.

I went to the City of Ten Thousand Buddha in January and most of the residents were in the midst of the final week of a three-week Chan meditation retreat. I dropped by the DRBU building and only a few staff were there. The entire building and the surrounding campus were completely silent. It was a wonderfully quiet feeling. The atmosphere was alert, clear, and crisp, yet quiet and pleasant. The spirit of shared collected effort across the campus gave it a sense of not solitude, not loneliness. I was trying to reflect on why that is.

A lot of the writers on our blog have been discussing and reflecting on the idea of loneliness and solitude and the idea of camaraderie. James had, in various living situations, found himself in situations where he spends a lot of his time in solitude. Alexandra in her response states that “solitude, on the other hand, is something that we choose for ourselves, or at least accept.” In a way, a communal, silent meditation retreat is a collective choice in group solitude–everybody practicing meditation, working on being totally concentrated in their own minds, together. Read More …

For the past several months, I’ve been part of a translation team that is working on the verses of the

Lotus Sutra. I think of translating as a practice; it contains a lot of different opportunities to learn about the Buddha’s teachings and about myself at the same time. I’ve been finding that translating verses in particular is a really wonderful practice, and like any Dharma practice, its benefits are gradually revealed as one delves more deeply into its subtleties.

The rhythm of a verse gets into your bones, puts a spring in your step. Its beauty inspires the heart.

A good verse can have some really wonderful qualities — it has its own rhythm, its own ways of resonating. A steady rhythm can be like a resting heartbeat, its regularity calming the mind. When chanted, regular line length regulates the breathing, which calms the body. The rhythm of a verse gets into your bones, puts a spring in your step. Its beauty inspires the heart.

I often chant while I’m translating, sometimes “working” for many hours a day, and I find that the rhythm itself has a way of inspiring creativity. Sometimes it is almost as if the translated verses appear on their own, without any effort on my part. I feel that I may be experiencing something described by many creative types, but also something that anyone who has spent time reciting a mantra, or has even gotten a favorite song stuck in their head, has probably touched upon. Read More …

… we are born with particular mental tendencies … and over time, certain tendencies are repeatedly reinforced, creating ever-deeper tracks for our minds to follow.

When the Buddha taught about the human mind, he put forth an idea that has been developed independently by psychologists and neuroscientists in more recent years: that we mainly interpret the world through deeply rooted habits of thought and perception, that we are born with particular mental tendencies – some that are universal to all humans, and others that are particular to each of us as individuals – and over time, certain tendencies are repeatedly reinforced, creating ever-deeper tracks for our minds to follow.

In some ways, these habits are very useful, and they probably developed to help us survive, enabling our ancestors in the jungle or the savanna to quickly learn the difference between a threatening tiger and a benign butterfly, for example. Thanks to mental habits, we do not have to start fresh with every tiger or butterfly we see, interpreting what it might be and how it might affect us. But in other ways, the limitations imposed by these habits can have profoundly negative consequences.

Recently, I’ve been confronted with this problem in the context of the criminal justice system. I have been working as a researcher and writer for the National Registry of Exonerations (NRE), a database that tracks cases in which an innocent person is wrongly convicted of a crime and later cleared of all charges. In each of these cases, police and prosecutors constructed a story about how and why a particular crime was committed– a story that later turned out to be entirely wrong. Read More …

ATLAS under construction, Source

On July 13th, UC Berkeley physicists, including Professors Beate Heinemann and Marjorie Shapiro – collaborators in the ATLAS experiment, explained the discovery of what could be the Higgs Boson. Their explanation of the decades long search for the Higgs Boson serves as an interesting comparison to Buddhist practice – not as a comparison of ultimate claims about the nature of reality, but a comparison of deep and prolonged investigations in subtle, invisible fields. This deep and prolonged investigation is at the heart of Buddhism as a personal practice, in contrast to Buddhism as a set of philosophical or religious assertions.

One of the vexing problems in quantum physics has been that the standard model used by quantum physics can explain forces like light and magnetism, as well as short range fields that exist at the atomic and subatomic level. But common everyday phenomena like gravity and mass have no explanation in quantum physics. Quantum physics, a physics of invisibly small particles and intangible fields, is still trying to explain these everyday phenomena. Read More …

[This is the fifth in a series of posts reflecting on how I found myself drawn to monasticism despite (or perhaps because of) my upbringing in the Bay Area and providing insight into how the relatively secular environment in which I grew up prompted me to look deeper into the meaning of life.]

Alas! My parents,

Who bore me and toiled on my behalf.

The debt of kindness I owe them

Is higher than the heavens.

– The Classic of Poetry

So there I was attending retreats and Dharma talks at a Buddhist monastery, learning from Buddhist monastics, and reading spiritual works that strongly emphasized the teachings on “filiality.” It was a teaching I agreed with: yes, I should repay the kindness of my parents–but whenever I went home and actually spent time with my mother, I had the impression I was making her miserable.

Of course, I could always justify my actions and my chosen path by reference to the life of the Buddha himself. Didn’t he run away from home in search of solutions to life’s deepest questions?

Was something wrong? Of course, I could always justify my actions and my chosen path by reference to the life of the Buddha himself. Didn’t he run away from home in search of solutions to life’s deepest questions? However, in the face of my mother’s displeasure, thinking like this didn’t help. (My dad wasn’t supportive either, but, being a lot more “hands off,” he would only tell me what he thought.) I felt caught. On the one hand, I didn’t want to make my parents unhappy; on the other, I needed to remain faithful to my aspirations and ideals, to be honest with myself.

In his talk, “Should One Practice Filiality,” Master Hua discusses how “great filiality” transcends one’s immediate family and extends to all beings. He explains that the way to truly benefit all beings is by helping them to put an end to suffering entirely. Simply providing material support isn’t enough. Read More …

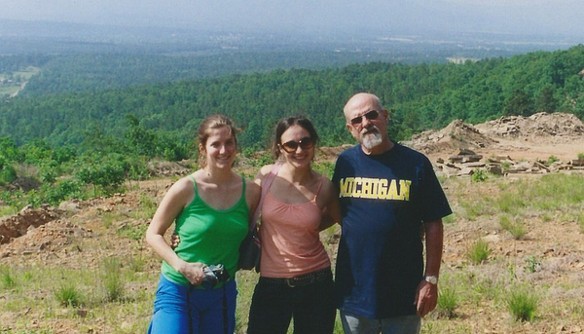

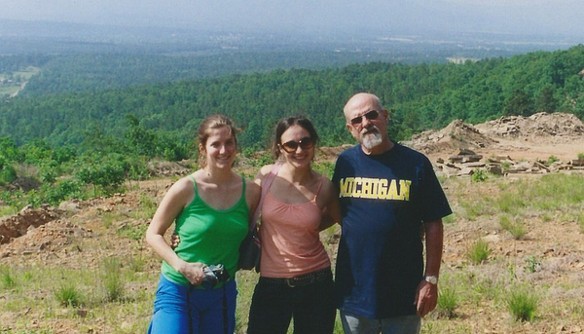

From a roadtrip that I took with a friend to visit Paris and his wife, Sherrie, in Oklahoma in 2005.

[Admin note: We’re very happy that Alexandra’s piece has been published on Huffington Post. Here is the repost in its entirety.]

Last spring, my friend Paris Carriger was diagnosed with liver disease and told he had just a few months to live. His voice from the hospital was weak but calm. “This isn’t the first time I’ve been sentenced to die,” he said with a raspy chuckle, “though I don’t expect I’ll beat this one.”

Thirty-five years ago Paris was wrongly convicted of robbing an Arizona jewelry store and killing the owner.

Thirty-five years ago Paris was sentenced to death for robbing an Arizona jewelry store and killing the owner. Paris said he had been framed by the real killer, a shady acquaintance named Robert Dunbar; he was arrested after police received a tip from a man who identified himself only as “Bob.” Years later, Dunbar admitted to the crime, but despite this confession Paris was denied a new trial, and remained on death row.

Paris grew up with a poor, abusive mother who sent him to reform school at 10. He led a chaotic life. But faced with execution for another man’s crime, he focused his energy. He wrote letters, dozens and dozens of letters to reporters, lawyers, activists and academics — anyone who might be interested in his case.

Eventually he began to correspond with my mother, a professor of psychology and law with a humanitarian heart and an old-school appreciation of good letter writing. Paris was a smart, engaging correspondent. My mother came to believe in his innocence, and to care about him. When I was 4, with my parents’ blessing, Paris first wrote to me. Read More …

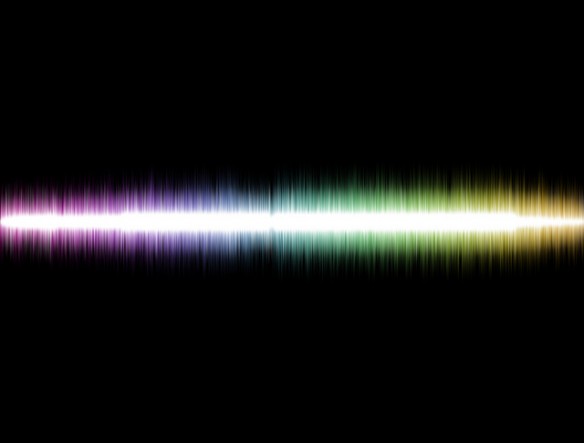

If a tree falls in the forest and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound?

With the upcoming Guanyin session, many of us at CTTB will be spending the week contemplating the nature of sound. Just as the Buddha was pragmatically agnostic when questioned about a world beyond perception, the Bodhisattva Guanyin also chose to investigate such issues through inquiries that directly address the meaning of the human condition: What would our experience be like if we listened as if each moment were completely new? Stated more formally, one would ask: If a sound arises, and the listener makes no distinctions of difference from mental habituations of the past, does the mind give rise to dharmas?

Looking closely, particles appear to exist as anything but discrete…. If one observes a single atom without perceiving its interconnected nature, is it really there?

Traditionally, science addresses such questions by disregarding anything outside of the empirical world. In science, sound is a vibration, and if a person measures it, it exists. Science claims to not be concerned with human meaning — but it turns out that this approach is not so clean-cut. Many findings in the quantum mechanical world require that scientists begin to question human meaning, and even the scientific process itself. Werner Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, for example, points out the problem of assuming that the world exists as discrete, measurable values. Looking closely, particles appear to exist as anything but discrete, rather distributed across all time and space as interconnected waves of energy. If one observes a single atom without perceiving its interconnected nature, is it really there? Contrary to our intuition, science and logic tell us that there is actually nothing there at all. Read More …

SHARE

SHARE EMAIL

EMAIL COMMENT6 comments

COMMENT6 comments