If a tree falls in the forest and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound?

With the upcoming Guanyin session, many of us at CTTB will be spending the week contemplating the nature of sound. Just as the Buddha was pragmatically agnostic when questioned about a world beyond perception, the Bodhisattva Guanyin also chose to investigate such issues through inquiries that directly address the meaning of the human condition: What would our experience be like if we listened as if each moment were completely new? Stated more formally, one would ask: If a sound arises, and the listener makes no distinctions of difference from mental habituations of the past, does the mind give rise to dharmas?

Looking closely, particles appear to exist as anything but discrete…. If one observes a single atom without perceiving its interconnected nature, is it really there?

Traditionally, science addresses such questions by disregarding anything outside of the empirical world. In science, sound is a vibration, and if a person measures it, it exists. Science claims to not be concerned with human meaning — but it turns out that this approach is not so clean-cut. Many findings in the quantum mechanical world require that scientists begin to question human meaning, and even the scientific process itself. Werner Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, for example, points out the problem of assuming that the world exists as discrete, measurable values. Looking closely, particles appear to exist as anything but discrete, rather distributed across all time and space as interconnected waves of energy. If one observes a single atom without perceiving its interconnected nature, is it really there? Contrary to our intuition, science and logic tell us that there is actually nothing there at all.

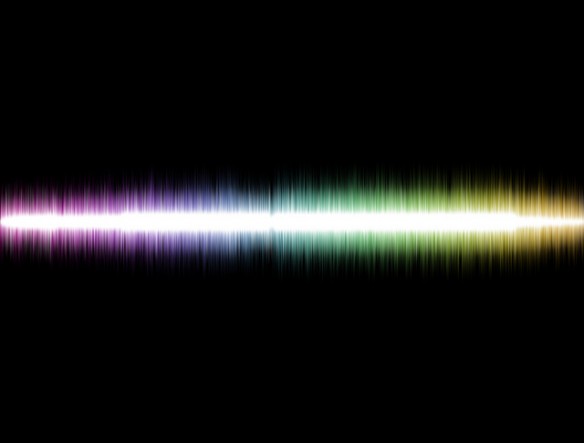

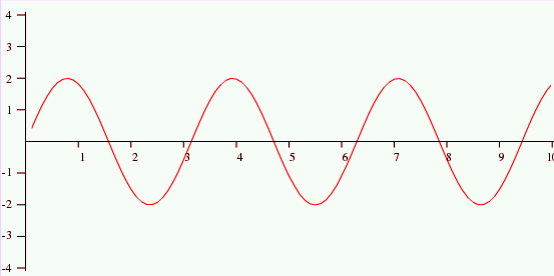

The field of musical acoustics, because it also attempts to discretely measure distributed properties of waves, encounters the same problem as quantum mechanics. For example, it’s widely understood that high pitches are more accurately perceived than low pitches over short durations.

Lower Frequency, less information

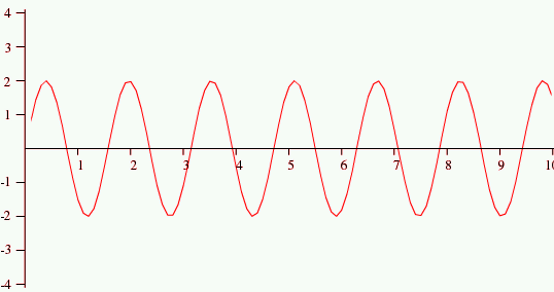

Why is this? In order for a sound to have pitch, it must have a waveform with frequency, which means that it must repeat over time. The more frequently a waveform repeats, the more information it contains about its frequency. Because of this, more information is contained in high frequencies than in low frequencies over the same duration.

Higher Frequency, more information

For better or worse, a sound can only contain the meaning of frequency if someone observes it and makes distinctions, looking for differences and comparisons with past experience.

It follows that in order to determine the entire harmonic spectrum of a sound wave, one would have to listen for an infinitely long duration, listening for differences as each waveform repeats in order to discern every harmonic. This is not only problematic in practice, but also conceptually: Although counterintuitive, the mathematical definition of frequency requires that it can only be exactly known over infinite spans of time. For better or worse, a sound can only contain the meaning of frequency if someone observes it and makes distinctions, looking for differences and comparisons with past experience. But without understanding all of time and space, what a sound actually “is,” as we imagine it, can never be known exactly. Both our perception and our idea of pitch are practically and conceptually flawed, and so the meaning that we create from them can only ever be a false shadow of reality.

Unlike quantum mechanical phenomena, both sound and their corresponding dharmas are directly perceived in the ordinary realm of human experience.

Rather than a seeing this as a curse, we could see it as a blessing. A person might want to understand how the mind perceives a world existing in terms of discrete times, places, and states, when empirically it appears that this is not the case. In Buddhist practice, we investigate this problem directly through the mind. As the Śūraṅgama Sūtra suggests, sound might actually be the best way to directly perceive the mind’s process as it interacts with the illusion of the sensory world. Unlike quantum mechanical phenomena, both sounds and their corresponding dharmas are directly perceived in the ordinary realm of human experience. We are constantly using our ears and our bodies to interpret sound waves as discrete mental events, or dharmas, our basic units of meaning. If we listen closely and carefully, we should also be able to perceive the process of this interpretation as it happens; and, according to Guanyin, to use this contemplation to see profoundly into the workings of the mind:

“I began with a practice based on the enlightened nature of hearing. First I redirected my hearing inward in order to enter the current of the sages. Then external sounds disappeared. With the direction of my hearing reversed and with sounds stilled, both sounds and silence cease to arise. So it was that, as I gradually progressed, what I heard and my awareness of what I heard came to an end. Even when that state of mind in which everything had come to an end disappeared, I did not rest. My awareness and the objects of my awareness were emptied, and when that process of emptying my awareness was wholly complete, then even that emptying and what had been emptied vanished. Coming into being and ceasing to be themselves ceased to be. Then the ultimate stillness was revealed.”

—The Bodhisattva Guanyin, from the Śūraṅgama Sūtra