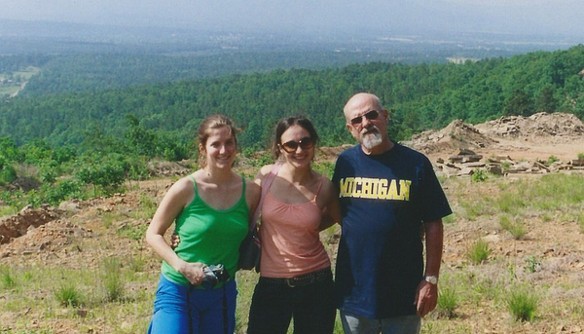

From a roadtrip that I took with a friend to visit Paris and his wife, Sherrie, in Oklahoma in 2005.

[Admin note: We’re very happy that Alexandra’s piece has been published on Huffington Post. Here is the repost in its entirety.]

Last spring, my friend Paris Carriger was diagnosed with liver disease and told he had just a few months to live. His voice from the hospital was weak but calm. “This isn’t the first time I’ve been sentenced to die,” he said with a raspy chuckle, “though I don’t expect I’ll beat this one.”

Thirty-five years ago Paris was wrongly convicted of robbing an Arizona jewelry store and killing the owner.

Thirty-five years ago Paris was sentenced to death for robbing an Arizona jewelry store and killing the owner. Paris said he had been framed by the real killer, a shady acquaintance named Robert Dunbar; he was arrested after police received a tip from a man who identified himself only as “Bob.” Years later, Dunbar admitted to the crime, but despite this confession Paris was denied a new trial, and remained on death row.

Paris grew up with a poor, abusive mother who sent him to reform school at 10. He led a chaotic life. But faced with execution for another man’s crime, he focused his energy. He wrote letters, dozens and dozens of letters to reporters, lawyers, activists and academics — anyone who might be interested in his case.

Eventually he began to correspond with my mother, a professor of psychology and law with a humanitarian heart and an old-school appreciation of good letter writing. Paris was a smart, engaging correspondent. My mother came to believe in his innocence, and to care about him. When I was 4, with my parents’ blessing, Paris first wrote to me.

I don’t remember the first letter I got from Paris. I don’t remember him coming into my life at all. He was just always there; a far-away pen pal, a friendly grownup presence who I knew only through letters and one greenish Polaroid of him standing with arms crossed in front of a metal grate.

… he told me about the things he loved to do as a child — fishing, riding horses, training dogs.

Paris wasn’t used to people letting him befriend their children, and he was deeply grateful to be allowed into my life. He was curious about my interests and the books I was reading, and he told me about the things he loved to do as a child — fishing, riding horses, training dogs. He sent me gifts on my birthday — binoculars, a pair of moccasins and, when I was 10, a typewriter that I began using to write to him.

In my child’s mind, jail was a spare, cartoonish space where people ate from compartment trays and wore stripes. I had no real sense of what his existence must have been like. I completely accepted that he was innocent, and understood, to some degree, that he was the victim of a great injustice. But really, I didn’t think about it that much. I sent him drawings and made him cards for Valentine’s Day and Christmas. I asked him how the food was (not good). I told him all about our new puppy and my part in the school play.

Sometimes, Paris’ insight into my experiences was better than my parents’. Once in middle school, I was bullied daily by a girl who said I had hugged her boyfriend — myself the victim of a false accusation. This girl followed me around the halls with a crew of friends, muttering insults and trying to trip me. When she pushed me up against the lockers, I called her the “b-word” and our parents were called in for a meeting with the principal.

My mother couldn’t understand why I hadn’t told her about this, but Paris completely got it. He wrote to her, “Sasha’s trouble looks different to me than it does to you. The biggest defeat would be to tell. Then she is branded a snitch and kids see her as the weaker one, the easy target.”

In eighth grade, given an English assignment to write about a person I admired, I chose Paris.

Despite Dunbar’s confession, despite other witnesses who admitted they had lied, he had lost all his appeals. He had been in prison for 18 years. An execution date was set: Dec. 6, 1995.

The reality of death row came into sharp focus when I was 14. Despite Dunbar’s confession, despite other witnesses who admitted they had lied, he had lost all his appeals. He had been in prison for 18 years. An execution date was set: Dec. 6, 1995.

My teenage mind focused on the horrors of execution itself. You exist today. You exist tomorrow. But at 12:15 a.m. on Dec. 6, you will no longer exist. What would it feel like to be informed precisely when you would be killed? It chilled my bones and made me sick.

He called more often. His voice, as usual, was calm and soft with a gentle southern drawl. I had no idea what to say to him. On my mother’s advice, I told him that. “Keep your chin up,” he said. “We may get out of this yet.” My mother travelled to the prison in Florence, Ariz., for his clemency hearing. Paris was there in a metal cage, his belongings already divided up among the guards, his body afflicted with shingles, his spirit with humiliation and the fear of death.

He wasn’t executed. On, Dec. 4, the Supreme Court upheld a stay of the execution to allow another appeal.

Three year later, with no advance warning, Paris was given $20 and a paper suit and let out the jail door. He set to work building a life from scratch, moving to Oklahoma to live with a long-lost half-sister. He came to visit us in Michigan. Incredible as it was to see him in person, he also seemed perfectly familiar; after all, I had known him forever.

My lifelong friendship with an innocent man on death row means that I have always been deeply opposed to the death penalty. I talk to people about it a lot these days with Proposition 34 and I urge them to vote “yes.” Those who favor it often say it’s too slow and expensive. I always think: “If we had a quick cheap death penalty, Paris would have been killed.”

Unfortunately, Paris didn’t live long enough to find out whether we will replace the death penalty in California. He died on May 21, at home with Sherrie, the woman he fell in love with and married several years after his release. The hospice workers said they had never seen anyone accept the end of life with such calm grace. Given how close he came to being executed for a crime he didn’t commit, I can imagine that dying at home was, in a sense, a victory.