[This is the fifth in a series of posts reflecting on how I found myself drawn to monasticism despite (or perhaps because of) my upbringing in the Bay Area and providing insight into how the relatively secular environment in which I grew up prompted me to look deeper into the meaning of life.]

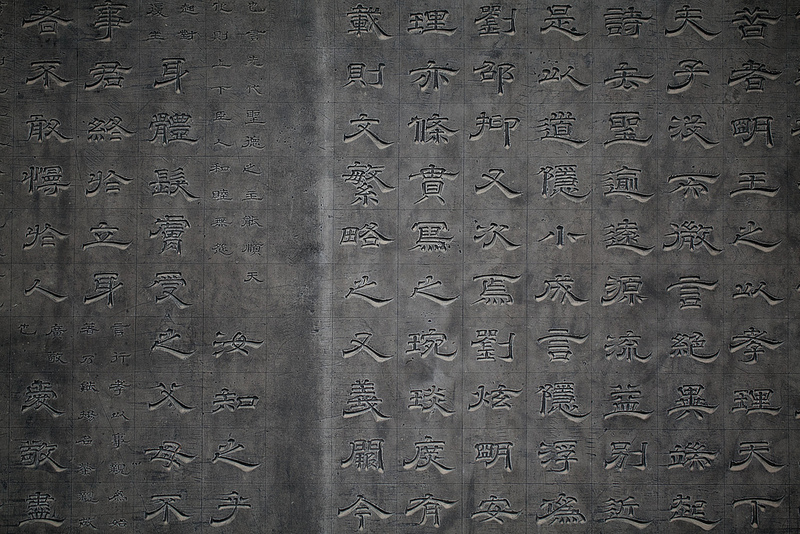

Alas! My parents,

Who bore me and toiled on my behalf.

The debt of kindness I owe them

Is higher than the heavens.– The Classic of Poetry

So there I was attending retreats and Dharma talks at a Buddhist monastery, learning from Buddhist monastics, and reading spiritual works that strongly emphasized the teachings on “filiality.” It was a teaching I agreed with: yes, I should repay the kindness of my parents–but whenever I went home and actually spent time with my mother, I had the impression I was making her miserable.

Of course, I could always justify my actions and my chosen path by reference to the life of the Buddha himself. Didn’t he run away from home in search of solutions to life’s deepest questions?

Was something wrong? Of course, I could always justify my actions and my chosen path by reference to the life of the Buddha himself. Didn’t he run away from home in search of solutions to life’s deepest questions? However, in the face of my mother’s displeasure, thinking like this didn’t help. (My dad wasn’t supportive either, but, being a lot more “hands off,” he would only tell me what he thought.) I felt caught. On the one hand, I didn’t want to make my parents unhappy; on the other, I needed to remain faithful to my aspirations and ideals, to be honest with myself.

In his talk, “Should One Practice Filiality,” Master Hua discusses how “great filiality” transcends one’s immediate family and extends to all beings. He explains that the way to truly benefit all beings is by helping them to put an end to suffering entirely. Simply providing material support isn’t enough.

Although this made a lot of sense to me, I didn’t know how much sense it would make to my parents, and I wasn’t sure how to tell them what I wanted to do in college. Being practical, I thought, if I was going to be a monk, I shouldn’t major in Computer Science or Engineering but in Chinese, so that I could better understand and assist in the translation of Chinese Buddhist texts. This, of course, was not kosher, because my mother, who was also practical, believed that, by majoring in Chinese, I was wasting my education. What kind of job would I be able to get afterwards? In the end, we compromised, and I chose to major in Physics, which I enjoyed, and which seemed to satisfy my mom, since it meant I would have more secure job options when I graduated. (Honestly, I don’t have a gift for languages–my Chinese is quite bad; so, in hindsight, I can see, and feel gratitude for, my mother’s wisdom.)

He harshly replied that I should figure out my own life and listen to my mother more. Rather unexpected!

While in college I also thought, if I was going to be a monk, I had better start preparing for it, so I started waking up at 5 or 6am to meditate–just the hour when my roommate was going to sleep! In addition I limited my food intake, and spent my free time reading Buddhist texts or visiting the monastery. Being determined to make this my life’s path, I was extremely gung-ho.

One day, I worked up the courage to ask a senior monk I deeply admired what I should do with my life, hoping he would give me some advice about becoming a monk. He harshly replied that I should figure out my own life and listen to my mother more. Rather unexpected!

But, in many ways, this was the turning point in my relationship with my mom. I saw how attached I was to the idea being a monk, as I imagined that in my own mind, and realized that I was approaching monasticism in a way that was unbalanced and harmful to my family. At that point I decided to transfer the energy I had been putting into “trying to prepare for monastic life” into “trying to be a good son”: I began to listen my parents more, which made a real difference in the quality of our relationship.