In a recent post, Patience and Solitude, James wrote about what it has been like to give up so much of his previous existence in order to live a simpler, more solitary life at CTTB. I was struck by his observations about the challenge of loneliness; it got me thinking about the differences between loneliness and solitude, and the relationship between the two.

Loneliness happens to us against our will, and we want to fight against it. It can be hard even to admit that you’re feeling lonely, because doing so seems like admitting that you are unwanted, insignificant and easily ignored.

Loneliness as we tend to understand it is negative and undesirable. Loneliness happens to us against our will, and we want to fight against it. It can be hard even to admit that you’re feeling lonely, because doing so seems like admitting that you are unwanted, insignificant and easily ignored. Solitude, on the other hand, is something that we choose for ourselves, or at least accept. Solitude has an important role in most spiritual traditions, and is also often required by artists, philosophers and other creative types.

Loneliness is agitated, uncomfortable and grasping, while solitude is a space from which stillness and clarity can emerge. But we don’t reach a clear and strong place of solitude automatically, just because we are alone. We have to work to get there, and loneliness is one of many obstacles that can arise along the way.

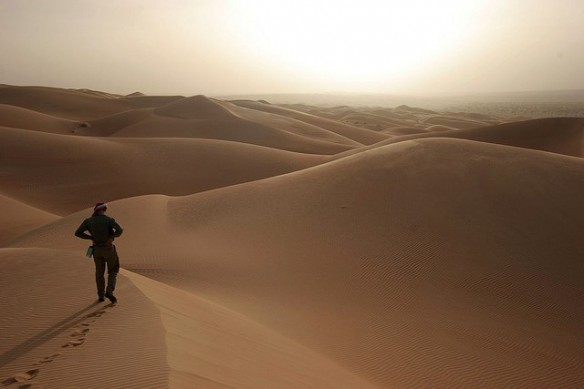

This struggle to accept solitude is captured in a piece written by Paul Bowles, called “Baptism of Solitude”, in which he describes the experience of the Sahara desert:

“You leave the gate of the fort or the town behind, pass the camels lying outside, go up into the dunes, or out onto the hard stony plain and stand a while, alone. Presently, you will either shiver and hurry back inside the walls, or you will go on standing there and let something very peculiar happen to you….”

This peculiar experience is the “baptism of solitude”, and it occurs only if you stay out there alone a little longer, rather than hurrying back inside at the first shiver.

“It is a unique sensation, and it has nothing to do with loneliness, for loneliness presupposes memory.”

“Loneliness presupposes memory” – to me, that means that loneliness depends on our pre-existing, habituated ideas about who we are and who we should be, our attachments to relationships and roles in the world. Solitude, on the other hand, is free of all this.

“Here, in this wholly mineral landscape lighted by stars like flares, even memory disappears; nothing is left but your own breathing and the sound of your heart beating.”

Habituated existence begins to fall away, revealing the underlying stillness. But to actually stay there, to surrender to a moment of free and solitary existence, is not easy.

“A strange, and by no means pleasant, process of reintegration begins inside you, and you have the choice of fighting against it, and insisting on remaining the person you have always been, or letting it take its course. For no one who has stayed in the Sahara for a while is quite the same as when he came.”

This process of reintegration, I think, is the process of accepting the freedom and stillness of solitude. In typical, paradoxical Buddhist fashion, it is the battle to stop battling, the internal struggle to stop struggling completely and give in to what is there.

So, if we are never lonely, have we lost our ability to connect? Are we somehow less human?

To get there, even just for a moment, we need to let ourselves move beyond loneliness. It could be that, as much as we don’t like to be lonely, the idea of being completely alone and not lonely is also strange and frightening. For most of us, a capacity for loneliness is part of the person we “have always been.” Loneliness is based on a desire for connection with others, a desire for community – human urges that are natural and generally considered to be positive. So, if we are never lonely, have we lost our ability to connect? Are we somehow less human?

I won’t try to address that huge question in this space, and I won’t suggest that we all try to plunge into extreme, unattached solitude whenever we feel lonely. Often, the best solution for the moment might be to call a friend, or write a letter, or get out of the house.

But I do believe that on a deeper level, we don’t have to reach out in order to find peace. Sometimes, instead of trying to get around loneliness, we can try to get through it. We can stay out on the dunes a little longer, we can surrender to the difficult process of confronting our mysterious, solitary self, which exists independently of our relationships, our work, our various roles in the world.

For a brief moment, maybe, we can see things from a different perspective, where loneliness and its anxious concerns suddenly seem to miss the point completely, stuck in the realm of the habituated self that clings to a limited, condition-based view of connection. Even if we don’t stay here for long, I think these moments of true solitude make us stronger.