What if perfection didn’t require any reference or comparison at all?

We tend to think of good things as being positive, of positive things being good. When things are perfect, for example, that’s something positive, right? Everything is just how you want it; everything is just so. But what if perfection didn’t require anything to be posited, to have a position, to be something positive as opposed to negative? What if perfection didn’t require any reference or comparison at all? What if perfection could be just what it is right now, not needing anything else; lacking nothing?

… she reflected on the idea of perfection as an ongoing process, one that never reaches completion, and by the very nature of this never ending journey, is in some way already complete.

A few weeks ago in Audrey’s post, The Presence of Perfection, she reflected on the idea of perfection as an ongoing process, one that never reaches completion, and by the very nature of this never-ending journey, is in some way already complete. This particular meme is pervasive in traditional Buddhist culture and literature, as is the metaphor of the perfection of emptiness; the perfection that lacks everything and thereby lacks nothing.

I’ve been spending some time working on translations lately, and I keep running across the word bǎo (寶) often translated as “gem.” Just like in English, and also in Sanskrit (ratna), it implies something precious and rare—for example, “That dharmas blog sure is a gem.” Read More …

… it is extremely difficult to stay alert and attentive instead of getting hypnotized by the constant monologue inside your own head. Twenty years after my own graduation, I have come gradually to understand that the liberal-arts cliché about “teaching you how to think” is actually shorthand for a much deeper, more serious idea: “Learning how to think” really means learning how to exercise some control over how and what you think. It means being conscious and aware enough to choose what you pay attention to and to choose how you construct meaning from experience. Because if you cannot exercise this kind of choice in adult life, you will be totally hosed.

— David Foster Wallace in a 2005 Commencement Speech to the graduating class of Kenyon college

“If you can deal with hot emotions, then you can study for the S.A.T. instead of watching television.”

In my previous post concerning the marshmallow study, I mentioned that being able to strategically allocate one’s attention is crucial to inner and outer happiness. There are practical, worldly benefits: “….this view of will power also helps explain why the marshmallow task is such a powerfully predictive test. ‘If you can deal with hot emotions, then you can study for the S.A.T. instead of watching television,’ Mischel says. ‘And you can save more money for retirement. It’s not just about marshmallows.’”

Wallace continued by saying:

The really important kind of freedom involves attention, and awareness, and discipline, and effort, and being able truly to care about other people and to sacrifice for them, over and over, in myriad petty little unsexy ways, every day. That is real freedom. The alternative is unconsciousness, the default-setting, the “rat race” —the constant gnawing sense of having had and lost some infinite thing.

Read More …

On our way back from a visit to Dharma Realm Monastery in Liugui, a rural district of Kaohsiung, Taiwan, our local host took us to visit another Buddhist establishment in the vicinity. This particular monastery sits half-way up one of the many hills in this mountainous region in Southern Taiwan, and like many other hill-side properties, fell victim to a particularly severe typhoon several years ago. The mountain top above the temple crumpled after days of heavy downpour and the mudslide buried or damaged significant portions of the temple.

Three years after the storm, much of the temple has been restored and even rebuilt. The grounds are spotless –residents and volunteers dust and mop daily, even the outdoor area and we are asked to leave our shoes at the front gate. The complex has a layout of a traditional Buddhist monastery, with a series of halls housing statues of different sages on an axis and a courtyard in the middle, and flanked by residential quarters for nuns and guests on two sides.

Read More …

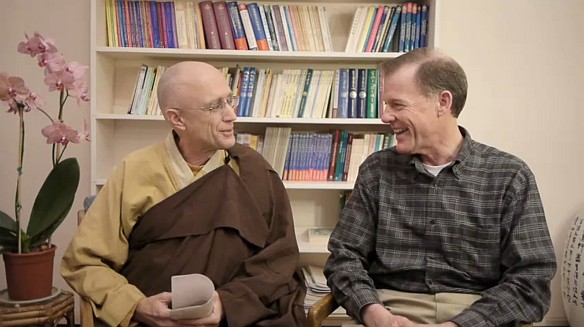

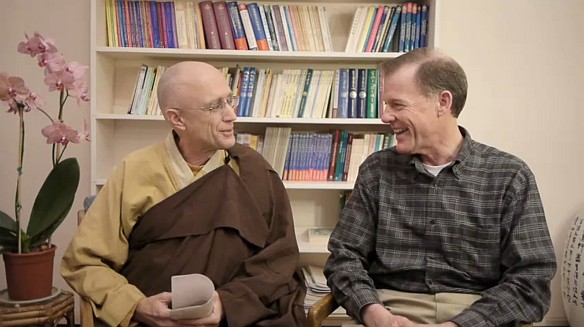

In January the Zen Chan Buddhist Catholic Dialogue took place at the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas. Among the twenty-two participants were teachers and monks from Dharma Realm Buddhist University, professors from Catholic Theological Schools, a representative from the American Council of Bishops and representatives from the Zen tradition on the West Coast.

The Dialogue is one of the longest ongoing Buddhist Christian interfaith dialogues in the country. The same group has been meeting once a year for the past nine years investigating salient issues among the traditions and discovering strong as well as weak, or forgotten, points of common interest.

[Web Link for further details about the gathering.]

[See video below of a short conversation between a Buddhist monk and Catholic Bishop about their ongoing interfaith dialogue] Read More …

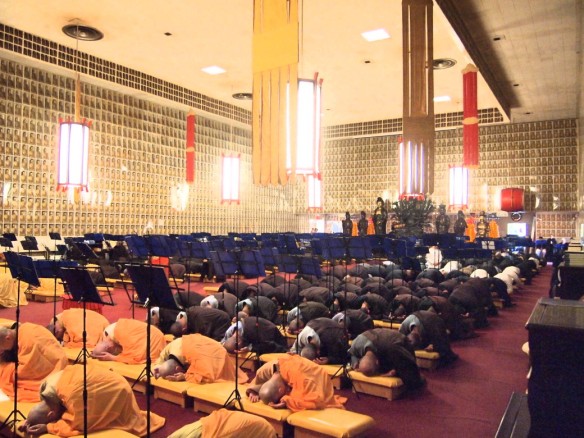

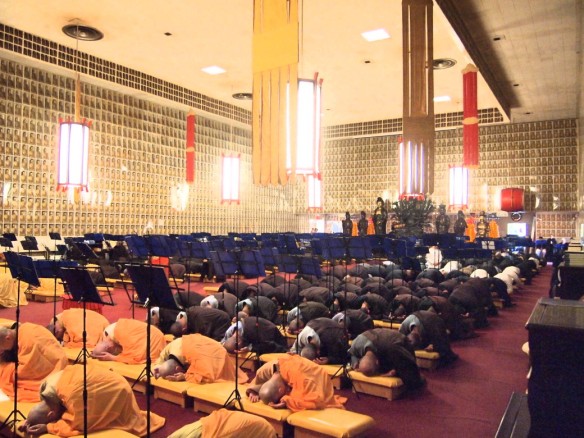

It was a slow, calming but also energizing practice. We did about five hundred bows every day, which took about six hours.

Shortly after classes ended in May, the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas hosted a bowing session for twenty-three days. During the session we bowed to the ten thousand Buddhas that our community gets its name from. Just as the Buddha Hall literally contained ten thousand Buddha statues, our bowing session literally consisted of ten thousand bows. We recited each Buddha’s name, and then bowing our heads to the floor, contemplated the name for several seconds, before rising again to recite the next name. It was a slow, calming but also energizing practice. We did about five hundred bows every day, which took about six hours. Even including the morning and evening ceremonies, and the lunch offering, the schedule of this retreat was not particularly intense, but it put a lot of demand on the body and the breath during those six hours, and after just a couple of days, I noticed my body, my breath and my attitude had started to shift in some significant ways. Read More …

We are now on Twitter and Facebook! We will provide content, links, and information on our Twitter feed and Facebook page. Please follow us on these social networks, and give us feedback on our content. We also welcome your suggestions and feedback about the website and blog. Please contact us through any of these sites, or send us an email at web@drbu.org.

Girls from the School

As the school year wraps up, we asked the 4-6th graders to reflect on what they learned in meditation class. Their responses were both insightful and simple, serious and witty:

I feel like my mind got a bath ….

“I think meditation has been helping me. Not only my behavior, but my mind. I feel that in behavior, I’m getting better at controlling my temper. Last year, we didn’t do much meditation, so I got sent to the office many times. My mind feels cleaner [now]. When we meditate and do those activities, I feel like my mind got a bath– a refreshing one. I think it’s all the focus, concentration, and deep thought.” Read More …

Recently, great posts by Alexandra and Audrey got me thinking. In their posts, along with my previous conversations with others who are trying to gain a little insight into their minds, often the word or the image of “edge” comes up.

Alexandra wrote about becoming aware of one’s subconscious thoughts, of going to the “edge of conscious awareness and stand[ing] there, staring into the darkness.” Audrey wrote an amazingly honest post about being on the “cultivator’s edge” of discomfort and upheaval.

For me, moments of that “edge” come up when I’m by myself, with no activities planned, and confronted with that nothing-space. Often, a nervousness comes up, and the need to switch on a computer, a TV or another device ensues. There’s an intersection between a reflexive following of that drive versus taking a step back and assessing what’s going on. It’s an ongoing, uncomfortable, and nebulous struggle not to follow that drive. Read More …

SHARE

SHARE EMAIL

EMAIL COMMENT4 comments

COMMENT4 comments