Before taking Doug Powers’ class on Buddhism and Postmodernity, I had only a vague idea of what people meant by “postmodernism.” I knew it had something to do with deconstruction, theory, and meta-narratives—but I wasn’t entirely sure what all that was about either, and frankly I wasn’t particularly interested. I was pretty certain it was a bunch of ivory tower jargon that people threw around mainly to show off, and I didn’t see much point in learning to understand it.

As I see now, my disinterest in these ideas was kind of ironic, because in so many ways, I am the product of this postmodern context. Doug’s class opened my eyes to larger cultural trends that have affected me all my life. In particular, it shifted my perspective on what it takes to work for justice and equality in this world.

Postmodernism, among other things, is a relentless attack on any idea that claims to apply universally to all human beings. This often involves rejecting anything considered to be part of the Western intellectual canon in favor of the works of historically marginalized groups of people such as women, people of color, and citizens of developing countries. For decades now, intellectuals have been fighting about what is and isn’t actually worth studying, and whether it is ever possible to privilege one kind of knowledge over another.

It’s amazing to me that I was almost entirely unaware of these debates while I was in college

It’s amazing to me that I was almost entirely unaware of these debates while I was in college; I attended an elite and decidedly left-leaning university that would seem like an ideal setting for these battles. Maybe the debates were limited mainly to the comparative literature and critical studies departments, or maybe the fight had been raging for so long by that time that it had faded into a kind of white noise in the background. Maybe there was no one conservative enough at Brown to have a real argument with. Or maybe it’s just that I was too busy actually living the postmodern dream to pay attention to the debates about why I should or shouldn’t be doing so.

I started college very troubled by a sense of worldwide injustice. I studied international development, taking classes on the political systems, sociology, and colonial history of developing nations so that I could understand, and then attack, the root causes of global inequalities. My friends and I drove hours to protest the meetings of international trade organizations, rallying against what we were vaguely calling “globalization.” I took classes in ethnic studies and postcolonial literature, but not the classes on why it was important to do this. I certainly didn’t subject myself to the Western Classics—it didn’t take a critical theorist to tell me how pointless that would be.

I now see how important it is to have a sense of the larger frames that shape who we are.

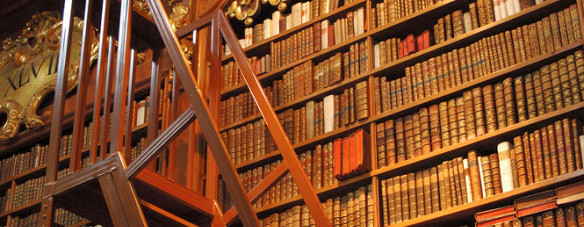

I don’t regret a thing about my college experience—I learned a huge amount and met many interesting and inspiring people. But there’s a lot more to learn. I now see how important it is to have a sense of the larger frames that shape who we are. We need to understand how we’ve been affected not only by postmodern thought, but also by the hugely influential Modern and Classical ideas that postmodernism critiques, but is also very much based upon. If you want to understand how to change the world, you have to understand your history, your motivations, yourself. It turns out that those infamous dead white males had some very interesting insights on how to do this. I can’t say whether or not their ideas apply universally, but I have certainly found many that resonate with me.

Eight years out of college, I have a lot of reading to do.

Eight years out of college, I have a lot of reading to do.