A couple weeks ago, my friend Jesse’s piece entitled “Strangers” won the 2012 Ippy Award for Best Photo Essay. He’s been working as an independent photojournalist for a number of years, having contributed to a number of publications, including Buddhadharma. He also practices at the Village Zendo, a “Zen temple in the heart of Manhattan.” Perhaps it goes without saying that Jesse has a keen eye for the conditions of the modern mind, and particularly within American Buddhist culture. Jesse recently finished another photo essay entitled “Ordinary Zen,” shown below. The essay features an intimate look at four Zen practitioners, through their own words and Jesse’s photos.

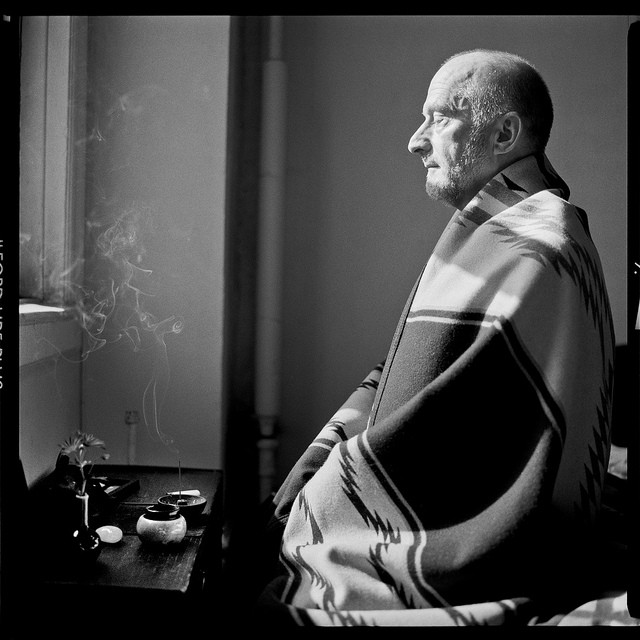

Bill Seizan Ewing

In 2002, I went to a yoga class and ran into a guy I’d had a longstanding spiritual discussion with. He said he’d spent a solid month in meditation with a bunch of Zen Buddhists. And I said, I would love that. Occasionally I used to spend a weekend not talking. I’d get together with one of my friends, someone I felt comfortable with, and I’d say, let’s do something this weekend, let’s not talk. You can come over to my house or I’ll go to yours, we’ll have a slumber party, and we’re not going to speak. We’ll let the conversation in the head chill out. So when I heard about a silent month, I thought that sounded weird and funky and great and I’d love to try that.

I got the schedule for the Village Zendo, and went to beginning instruction. I was comfortable sitting on the floor, I had no problem, and the instructor said, let’s do this for five minutes, just count your breath up to ten and then start over. I got up to thirteen before I remembered to go back to one!

I’ve been dancing Tango for six years. At the first lesson, you stand, with your posture really straight, put your hands on your stomach, breath so that you can feel your stomach—it’s this whole physical thing. Tango is really Zen. You have to be in the moment, right there with the person you’re dancing with. Your awareness goes, not just to your center of gravity, but to the center of gravity you’re creating together. And when you connect like that, that’s Tango. You’re moving as one body. The feeling is like nothing else.

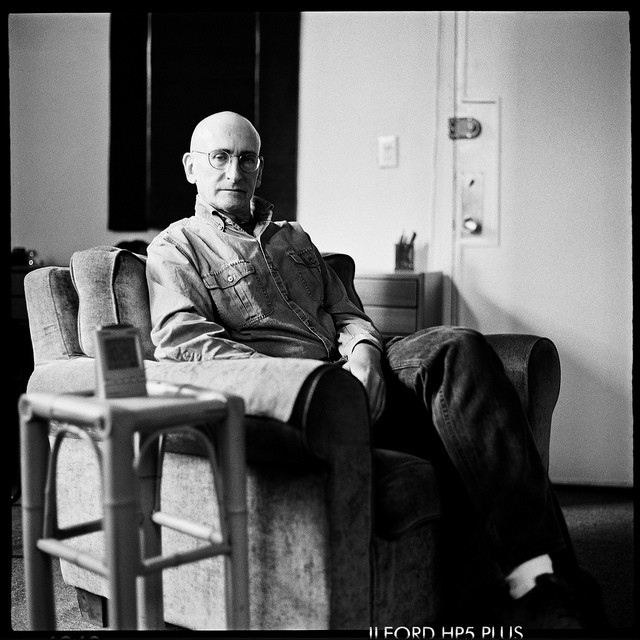

Jean Yugetsu Carlomusto

I’m one of the most un-Zen people on the planet. No one would ascribe Zen to me. It’s because they misunderstand what Zen is. They think Zen is the buddha sitting strong—and that’s true. But there’s also the Buddha having a screaming fit at the dog for peeing on the rug. That is all part of the Buddha way. What elevates it is that you try to be aware of it at every moment. That’s the hardest thing.

I do think that the practice oftentimes changes people, but not because they want to change. Rather it’s because they’re seeing themselves in a way that permits them to behave differently. Because they’ve studied themselves.

I got into Zen through Enkyo Roshi. Roshi was my professor, and one day after I graduated I saw her on the street, and her head was shaved. The first thing I thought was, I hope she’s ok. She said, we’re sitting at my apartment. I’ve become a Zen priest.

I started going to the Village Zendo in the early 90s. I was working at Gay Men’s Health Crisis, and at ACT UP. All then the people I was close to started to die, and I was drained. There was a period of time for about a year when I didn’t want to go out. I just stayed home. And the meditation helped me recover some kind of savoring of life.

Emma Seiki Tapley

I got into Zen because my mom was into Zen. I was 23. I went to the zendo and got very formal instruction. It felt like hell. I thought, my mom obviously wants to kill me. When is it going to be over?

Enkyo Roshi married me and my husband. (Now my ex.) At the time I had a lot of reservations about getting married, but when she showed me what I was agreeing to, I thought, I can agree to this. That’s when I started practicing.

I go to the morning sits at the Zendo. I’ll wake up and read the paper in bed and read some emails, and then I’ll walk over. When I can, I go five mornings a week.

I can’t remember which came first, my art or Zen. I’m becoming comfortable taking longer with my work, and as a consequence the paintings are getting better. And that comes from sitting. Slowing down. People are not into that—they appreciate it, but they’re not into it.

When I first started, I felt like I could see things more clearly than other people, which is super-toxic. I’m glad I’m over that. I remember once, when I was with my husband, I felt he was so lost. But now, I’m really lost.

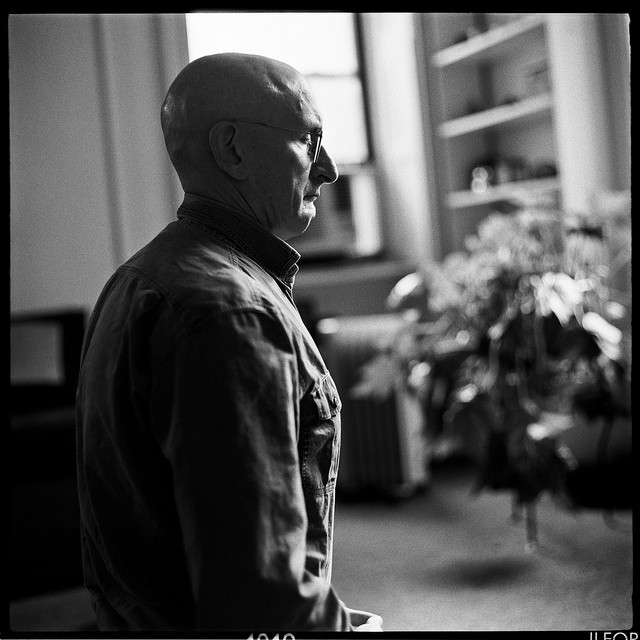

Randall Ryotan Eiger

In about 1978 I’d just had a really bad breakup with a girl and I was moping around, and my roommate said, “Read this. It’ll make you feel better.” It was Alan Watts’s The Way of Zen. When I read it I said to myself, I have no idea what this is about, but whatever it is, this is the truth. It reminded me of Beckett. I thought, I have to find out about this. I started reading a lot of books about Zen. I didn’t start sitting, but I read a lot of books for the next seven or eight years.

In 1988 I got an invitation to a writers workshop at Zen Mountain Monastery. I didn’t want to go, it was the middle of February, and going up to the Catskills in winter didn’t appeal to me. But my wife said, go, you’ll like it, it’s Zen, it’s writing. So I went, and I started my sitting practice there, on February 16, 1989. I was 35.

For the first five or six years I was in intense pain. My body is the kind of body that doesn’t like to do that sort of thing. If someone had worked with me on the physical side of it that might have helped but no one did. After three periods of meditation I was scraping myself off the floor.

Some time in my 30s I became a therapist. Because I come from a Zen perspective I’m not interested in curing people. I just let them sit with their hellish problems. I’m fine if there’s no progress at all, because I firmly believe that it’s by going into the problem that you begin to untangle the knot.