[This is the second of a series of posts reflecting on how I found myself drawn to monasticism despite (or perhaps because of) my upbringing in the Bay Area and providing insight into how the relatively secular environment in which I grew up prompted me to look deeper into the meaning of life.]

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

Reading by Shramanera Chin Wei. Click the arrow on the audio player above for the audio. You can also download the recording.

Spiritual nakedness [without masks] is far too stark to be useful. It strips life down to the root where life and death are equal, and this is what nobody likes to look at. But it is where freedom really begins–the freedom that cannot be guaranteed by the death of somebody else. The point where you become free not to kill, not to exploit, not to destroy, not to compete, because you are no longer afraid of death or the devil or poverty or failure. If you discover this nakedness, you’d better keep it private. People don’t like it. But can you keep it private? Once you are exposed… Society continues to do you the service of keeping you in disguises, not for your comfort, but its own.

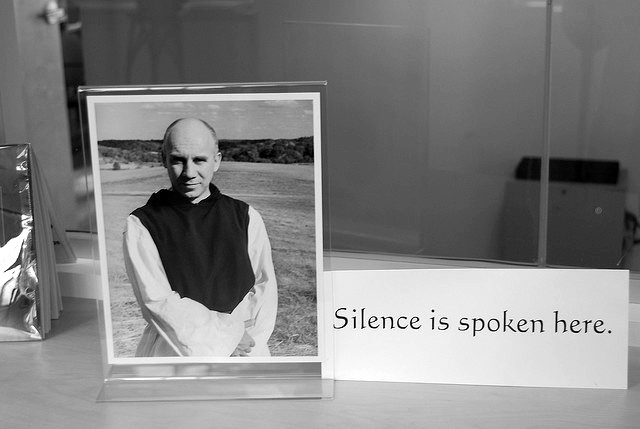

-Thomas Merton, Learning to Live

… words that cut right to the heart of things, not with the blade of cynicism and satire, but with clarity and compassion.

The writings of Thomas Merton, Master Hua, and Ajahn Sumedho struck a chord with me. Somehow, while reading them, I knew what I was reading were “true words”–words that cut right to the heart of things, not with the blade of cynicism and satire, but with clarity and compassion. Merton revealed life in its bareness and simplicity, removing the pride, the show, the falseness.

The Buddhist teaching of Great Compassion links all beings together as one family, as “one substance.” I remember reading a poem by Master Hua:

Truly recognize your own faults.

Don’t discuss the faults of others.

Others’ faults are just my own.

Being of “one substance” is Great Compassion.

This poem points to the deeper connection all beings share: we are not separate but of “one substance.” The mistakes others make are my own mistakes, and I have a deep responsibility for the well-fare of others. I connect this idea with the Christian idea of agape, or unconditional love.

… is quite different from that of Holden, the narrator of The Catcher in the Rye.

The attitude of Great Compassion is quite different from that of Holden, the narrator of The Catcher in the Rye. Although this book also indicates an underlying truth by exposing the hypocrisy of what society conspires to call “life”, it presents a rather bleak picture of society. If Holden were to meet himself on the street, I think he would consider himself pretty “phony” as well.

I soon realized that my life’s heroes were these monastics who strove to live a life of simplicity as authentically as possible, a life dedicated to ideals and guided by principles.

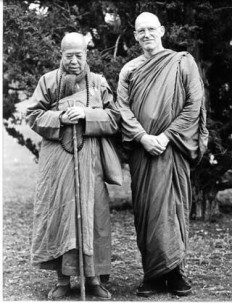

Picture of Venerable Master Hua & Venerable Ajahn Sumedho, whose meeting represented a coming together of the Northern (Mahayana) and Southern (Theravada) strands of Buddhism.

In Four Noble Truths, Ajahn Sumedho says:

The Pali word, dukkha, means “incapable of satisfying” or “not able to bear or withstand anything”: always changing, incapable of truly fulfilling us or making us happy. The sensual world is like that, a vibration in nature. It would, in fact, be terrible if we did find satisfaction in the sensory world because then we wouldn’t search beyond it; we’d just be bound to it. However, as we awaken to this dukkha, we begin to find the way out so that we are no longer constantly trapped in sensory consciousness.

This seems to me a very mature approach to suffering, since here suffering is not seen as something to push away but as something to understand and “awaken to.” Suffering spurs us to look for something beyond the conditioned world. And that is what I myself was looking for. And that was why when I watched the video about the Trappist monks, I suddenly realized what I wanted to be “when I grew up”–I wanted to be like them.

At that time, although I knew my heroes were monks. I still didn’t know what kind of monk I wanted to be, Catholic or Buddhist–but I knew I wanted to be a monk.

Works Cited:

1. Merton, Thomas. “Learning to Live.” Love and Living. New York: Farrar. 1979. Print

2. Sumedho, Ajahn. Four Noble Truths. Amaravati Publications.