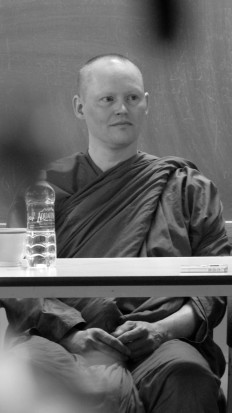

Ajahn Jotipalo

As part of the University’s Monastic Immersion Program this Summer, monks and nuns from different Buddhist traditions gave talks as guest speakers on topics ranging from the basic features of the Buddhism they understand and practice, the common spiritual exercises in their traditions, why they chose to “go forth” and enter the monastic order, and what attracted them to their particular traditions.

One of these guests was Ajahn Jotipalo. He is one of four monks from Abhayagiri Monastery in Redwood Valley, California, about twenty minutes’ drive north from the DRBU campus in Ukiah. In the evening of their day of the program, these monks—Ajahn Pasanno, the abbot of Abhayagiri Monastery, Ajahn Jotipalo, Kassapo Bhikkhu, and Sāmanera Suddhāso—took turns talking about how they entered the monastic life. They also answered questions from the students on a variety of subjects. Ajahn Jotipalo’s story struck a chord with me.

Already frustrated with having to clean a small space with nine other people, he all of a sudden found himself craving for a donut.

Ajahn Jotilpalo, who is from Indiana and has been a monk for more than 10 years, told the students what led him to Buddhism, and the experiences he had when he and a lay supporter wandered north along Highway 61 from New Orleans. However, it was his reflection on a seemingly mundane matter that stuck with me. In answering the question, “What’s the most difficult part of the monastic training?” Ajahn Jotipalo related a realization he had while cleaning the kitchen stove one afternoon. Already frustrated with having to clean a small space with nine other people, he all of a sudden found himself craving for a donut.

For us “householders” (basically non-monastics), if the craving is strong enough we would simply find a donut at home or from a store to satiate the craving. However, as a monk observing the vow of eating once a day at noon, Jotipalo couldn’t do that. Further, because monks rely on the lay community to donate food, he couldn’t simply ask for a donut. At that point, rather than taking the common view that these rules are restricting his “freedom,” Jotipalo used these rules as tools to help him reflect within—as the practice of upholding precepts is supposed to do.

…which means that eating a donut when we have the urge is an exercise of freedom, and therefore, Homer Simpson is the epitome of freedom.

He saw that the deep craving that we all have, manifested that afternoon in the form of a desire for a donut, is one of the strong forces that drives us to myriad actions. However, most of us either don’t notice it, don’t examine it, or chalk it up to “human nature” and surrender to its free rein on us. Jotipalo’s reflection on his craving for a donut—a common experience we all have at some point in our lives—is an elegant way to illustrate a basic Buddhist principle that Jason wrote about in his recent post “Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness.” Jason cited Bhikkhu Bodhi in describing what freedom likely means to most of us in the modern world: “We identify freedom with license, the freedom to act on impulse,” which means that eating a donut when we have the urge is an exercise of freedom, and therefore, Homer Simpson is the epitome of freedom.

donuts....

The likely ensuing chuckles mean that we probably recognize the absurdity of that statement, that we agree with David Foster Wallace in characterizing this conventional notion of freedom as “unconsciousness, the default-setting, the ‘rat race’—the constant gnawing sense of having had and lost some infinite thing.” During the same speech (which Jason also cited in his post), Wallace also noted that without the ability to exercise a different kind of freedom, we “will be totally hosed.” Finally, to Wallace, the “real freedom” is the kind that “involves attention, and awareness, and discipline, and effort, and being able truly to care about other people and to sacrifice for them, over and over, in myriad petty little unsexy ways, every day.”

What Jotipalo’s account shows is the efficacy of the practice of Sila—moral discipline of body, mouth and mind—in bringing these deeper undercurrents of our lives—often the very things we assume an identity with and therefore are blind and subservient to—into an arena so that we can wrestle with them.

I am sure many of the hundreds of people at the commencement ceremony at Kenyon College in 2005 nodded their heads as Wallace gave his speech and thought it made good sense. Many may even strive to live “consciously,” whatever that may mean. But as we can plainly recognize in the example of the donut, sometimes what we are struggling with is not necessarily what we can make sense of or something we can analyze and think our way out of. So what methods can we use to actually live the real free life that Wallace alluded to? What Jotipalo’s account shows is the efficacy of the practice of Sila—moral discipline of body, mouth and mind—in bringing these deeper undercurrents of our lives—often the very things we assume an identity with and therefore are blind and subservient to—into an arena so that we can wrestle with them. Even if we cannot defeat them right away, it’s better than the alternative, because if we cannot even see them, we have no chance to be free.